Research Revolution: Why Everyday Medical Decisions Need More Science

How can a physician know when a treatment actually works? Let’s examine the case of outcomes for patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. In a recent study, patients with the diagnosis were randomized to receive either an antibiotic or a placebo; the outcome measure was the proportion who developed symptomatic bacteriuria. The findings? Both groups had nearly the same proportion of symptomatic bacteriuria at the end of the study.

How can a physician know when a treatment actually works? Let’s examine the case of outcomes for patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. In a recent study, patients with the diagnosis were randomized to receive either an antibiotic or a placebo; the outcome measure was the proportion who developed symptomatic bacteriuria. The findings? Both groups had nearly the same proportion of symptomatic bacteriuria at the end of the study.

Clearly, the antibiotic made no difference in outcomes. But this can be a hard sell, not only for patients who expect their physicians to “do something,” but also for physicians, who believe that “doing something” is more responsible than doing nothing.

Assessing Effectiveness Requires a Comparison

To untangle this conundrum, we first need to define what we mean when we say a treatment “works.” It “works” if a specific test or treatment plan adds to the proportion of patients receiving a good outcome versus the proportion receiving a good outcome with another, alternative test or treatment plan. Simply put, a treatment works only if it adds more good than the alternative test or treatment plan.

Determining what works requires a comparison, a competition of sorts, where one treatment plan is studied in hopes of advancing the proportion of outcomes that are good for patients. Without comparing, nothing can be said about the value of a given test or treatment. We are always trying to improve outcomes for patients. The only way we can improve is by advancing “on the margin.”

Good Medical Decisions Depend on Marginal Differences in Outcomes

In fact, the margin is all that matters in medical decision-making. There cannot be a value to doing something when that something does nothing more for patient outcomes than some alternative. I am not sure if any of us would pay more for, or accept more risk for, any item if we did not believe the item improved some important facet of our lives.

Never can we do our best for patients if we offer tests or treatments that can’t be proven to better their well-being. We deliver the greatest value of care by doing the easiest, safest and least costly things when there are no real gains from more complex, dangerous and costly alternatives. Only knowing the margin helps us decide. And a treatment “works” only if there is a marginal improvement compared to an alternative.

The positive message: Often, less is more. Patients would agree, if we would just tell them.

But, some physicians may argue, patients will want something if they know they have bacteria in their urine: “If I send them away without an antibiotic, they will be unhappy.”

This brings us to the second part of our conundrum—physicians’ reluctance to “do nothing.”

The Decision to Treat Must Rest on Proof of Improvement

In a paper published in the Yale Journal of Biological Medicine, 2013; 86:271-280, the authors review and list the studies that suggest that there is a bias for action among physicians. This paper also hypothesizes why this bias exists. In the case of asymptomatic bacteriuria, just the act of giving an antibiotic seems to be additive—better than to doing nothing at all. The act itself appears to be a meaningful outcome measure. Doing nothing for a patient with this clinical state, so this argument goes, would lead to concern that the physician would be uncertain of the patient’s outcome and would feel poorly if she developed an infection.

Bias is an inclination to hold a perspective at the expense of an equally good alternative. Bias, at its core, violates the principle of marginal differences in medical decision-making by ignoring the alternative.

We cannot say what the patient would prefer unless we present the alternatives and explain actual differences in meaningful clinical outcomes. It is never justified to propose a test or treatment based on a bias or a belief if that belief cannot be shown to provide a marginal, added benefit. No studies demonstrate whether giving an antibiotic versus nothing for asymptomatic bacteriuria would be beneficial in any sense to a patient. Hence, giving a test or treatment just for the sake of giving it would never be justifiable medical practice.

This definition of “works” forces us to contemplate the alternatives, contemplate the differences between alternatives, and contemplate if the outcomes on which we are basing our decisions are meaningful enough for patients. Too often, unsafe and poor quality care, when the root cause is determined, can be traced to a failure to think and make good medical decisions on the “margin.”

Founded in 2002, ICLOPS has pioneered data registry solutions for improving population health. Our Population Health with Grand Rounds Solution engages providers in an investigative, educational process to achieve better outcomes. ICLOPS is a CMS Qualified Clinical Data Registry.

Contact ICLOPS for a Discovery Session.

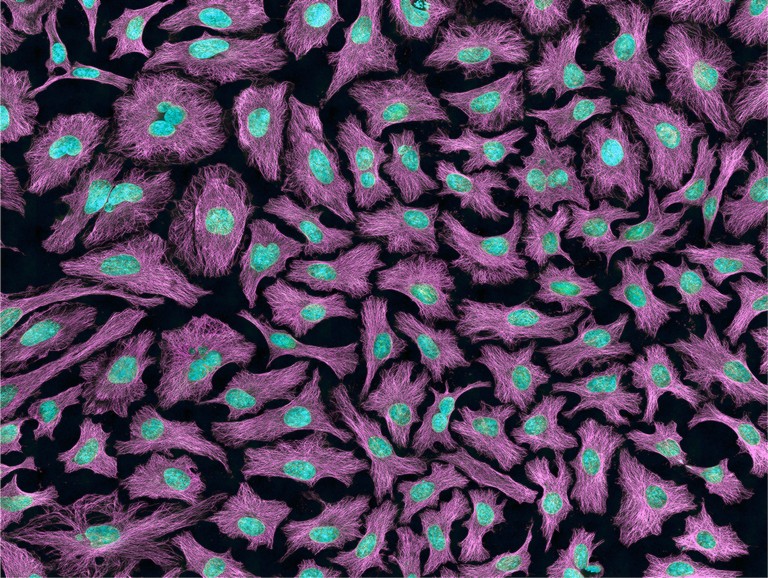

Image: HeLa III. “Multiphoton flourescence image of HeLa cells with cytoskeletal microtubules (magenta) and DNA (cyan). Nikon RTS2000MP custom laser scanning microscope.” National Institutes of Health, 2013.