In the rancorous public debate about how to provide health care to Americans—and especially to vulnerable people with higher risks, lower income, or both—there is a common explanation for rising costs: it’s the patients’ fault. According to this argument, we need to stop the “overuse” of health care services by consumers that are causing our costs to skyrocket.

But what if consumers really wanted to be excellent, cost-effective purchasers of health care. Could they actually do it? Could they legitimately question their physicians about recommended treatments?

There is little argument that the system of financing health care has immunized both providers and patients from the full cost of health care. But benefit plans that insulate consumers from any costs have disappeared from the market, and most consumers now have heavy deductibles and co-insurance provisions that tax them for received health care services.

Consumers motivated to purchase cost effective care need two essential tools: real costs and actionable information. Health care cost—known as price transparency—is not yet a reality. But if costs can be estimated, can consumers get enough information to support good decisions?

Unfortunately not, and here’s why:

Access to Patient’s Own Health Care Data Is Insufficient

Patients don’t have enough information about their own health status for a variety of reasons. In part, this is due to where the information lies—either in paper records or in providers’ Electronic Health Records (EHR) systems.

Even if the provider has an EHR, patients don’t always have access to their personal data. At best, they may be able to see or download test results, but will not see physician notes, diagnoses, visit data or synopses of treatments prescribed. That means that patients are universally required to remember exactly what was said during a visit, including medical terminology used, as well as treatment explanations. Health care is always provided in an “immediate” timeframe, which can stymie patients’ efforts to deepen their understanding.

Specifically, without access to data that the physician used to make determinations—which could include unmentioned physical exam details—patients universally have no recourse later to investigate. This is one reason why access or ownership over patient health records is an issue. Unless patients can retain all the details of their own health status, they do not have the power to independently investigate their options.

However, consumers have demonstrated that they want access to their health data and will use it. Indeed, there is a growing movement of consumers who are demanding better information and data in order to make better health care decisions.

Access to Medical Research and Clinical Trials Is Even Worse

Even minimal information to investigate conditions and treatments—for example, a CT scan report—would potentially provide a diligent consumer researcher with enough fuel to investigate severity and risk, and certainly more information for discussion with the physician.

That investigative journey would still be arduous, but could yield some real information. A nice itinerary of the process reveals some of the tools consumers could use. Nonetheless, there would be many dead ends, simply because consumers currently can not access research results.

Research falls into two categories: (1) medical studies on disease, progression of disease, causes, markers and effectiveness of various treatments; (2) pharmaceutical and device research (“clinical trials”) and other privately funded research in various dedicated medical areas, such as genetics and laboratory tests. Medical studies are often funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and account for less than half of all research. Clinical trials are funded by pharma firms and other private companies and account for more than half of total spending.

Access to the two types of research is dramatically different, with medical studies sometimes accessible—but not always. Consumers can find medical journal abstracts through the national database on PubMed, and, occasionally, general conclusions. However, finding the full article on the published journals and relevant data is harder. It’s also expensive. Prices for journal access range from $84 for 24-hour access to hundreds of dollars for unlimited periods.

Because all NIH funded research must be available to consumers, some full articles are available for free through PubMed Central or, infrequently, publishing journals’ websites. Hopefully, the number of free articles will grow due to federal funding requirements. Email requests of an article for personal use is another option. But the process, even for the most determined consumer, is daunting and likely impossible for patients trying to access multiple articles.

The lack of medical research data is bad news for consumers. Given the history of researcher competition, there is growing agreement in health care and even political circles that change is long overdue. As for pharmaceutical research, the hunt is tricky even for knowledgeable consumers. Pharma trials that show poor results are abandoned early on, with no published results.

The Quest for Truth in Clinical Research

Accessing medical research is challenging enough. Then there’s the question of the study’s veracity. The data is not always true, or the study design is bad. Clinical trials go through several phases, and early promising results may be completely overturned by later phases.

Unless consumers are very sophisticated, they may not be able differentiate good research from poor research. The good news, however, is that they can learn the basics of how to analyze studies.

How Can Physicians Help Patients Be Informed?

Physicians can and should be the curators of medical information for their patients. However, it will take a push from their patients to make that happen.

Patients must gain the confidence to understand the basic concepts of health care, even as they have been trained to defer judgment to their physicians (by the medical community). These concepts are key:

- Medical science is always on a continuum, because it is a discovery process. Therefore, it is essential to question whether what “we knew” is still correct.

- Decisions weighing benefit and harm should be made by the patient.

- Asking simple questions will lead to knowledge of benefit vs. harm—or to the alternative of recognizing that not enough is known.

With these concepts in mind, there are realistic actions that patients can take to obtain information from their credible source, their physicians:

- Patients should ask their physicians to provide literature for major diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Physicians will then be cued to their patients’ concerns and desire for further information.

- Patients should ask for a second opinion and also review literature with the consulting physician.

- When options include both pharmaceutical and procedural approaches, patients should seek consulting opinions from both medical and surgical specialists.

- Patients can use the specialty websites to further review research pertinent to their conditions or procedures for discussion with their physicians, and access patient advocate websites as well. However, note that advocacy websites are often directly funded by pharmaceutical and device companies, which should be taken into account.

- Finally, patients should question physicians and investigate whether specific research has been done related to their particular circumstances, such as age, gender, race, physical capabilities or chronic conditions.

Physicians aren’t all busy poring over medical journals, but they have the resources to help patients weigh their options and guide them through medical knowledge and patient decision-making. That will take work from both physicians and their patients, and time for consumers to get accustomed to evaluating health care just as they do other purchases.

In the meantime, the health care industry needs to understand that consumers aren’t “over-users” by choice. They have often been guided to that end by experts, and they haven’t had the tools to choose wisely.

Founded as ICLOPS in 2002, Roji Health Intelligence guides health care systems, providers and patients on the path to better health through Solutions that help providers improve their value and succeed in Risk. Roji Health Intelligence is a CMS Qualified Clinical Data Registry.

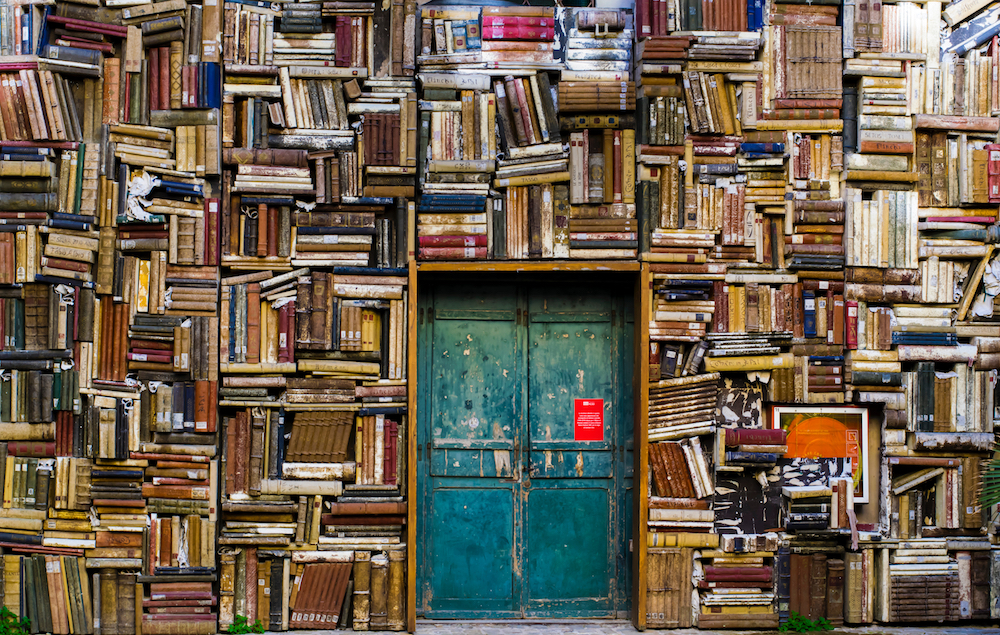

Image Credit: Eugenio Mazzone