What’s the Score? Decoding the MIPS Scoring Methodology

CMS is calling MIPS the “First Step to a Fresh Start.” When it comes to scoring, that’s an understatement. Although MIPS’s foundations are rooted in existing programs, the MIPS algorithm is a significant departure from today’s quality, cost and health information technology scoring.

CMS is calling MIPS the “First Step to a Fresh Start.” When it comes to scoring, that’s an understatement. Although MIPS’s foundations are rooted in existing programs, the MIPS algorithm is a significant departure from today’s quality, cost and health information technology scoring.

Not only new, this scoring methodology is complex. Providers will receive one aggregated MIPS Composite Performance Score (CPS), but remember—this one score is going to account for three existing programs, plus a component for ongoing improvement. The real first step: learn how the scoring is done. With penalties starting at 4 percent the first year, growing to 9 percent by the fourth, you must understand now what goes into your CPS.

CMS anticipates that the overwhelming majority of providers will be “MIPS-eligible.” It’s true that MIPS-derived payment adjustments will not begin until 2019, but the performance measurement year for those adjustments is 2017—less than six months away.

The Basics

The MIPS Composite Score is calculated by rolling up four categories. They’re weighted differently, and these will change as MIPS evolves. For the first year, here are the proposed categories and their first-year weights:

- Quality: 50 percent

- Resource Use: 10 percent

- Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA): 15 percent

- Advancing Care Information: 25 percent

Also critical: each category’s score will be converted into points. The point system is based on deciles, meaning there will be 10 possible tiers. The all-or-nothing scoring that’s been a staple of previous programs is being phased out. Even programs with a sliding scale, like the Value Modifier, have far fewer increments than this decile-based point system. Like VM, these will be calculated according to the group’s standing compared against others.

Quality

The Quality component accounts for half of the overall MIPS composite. Its roots are in PQRS and the Value Modifier, so let’s start with what’s changed:

- Only 6 measures will be required, rather than 9.

- There will be no National Quality Strategy (NQS) Domain requirement; in PQRS, 3 NQS domains are required.

- An outcome measure is required, in addition to a cross-cutting measure. Only the cross-cutting measure is required in 2016 PQRS.

- Reporting will be nearly comprehensive (80 percent through claims, 90 percent via Registry/QCDR/EHR), rather than the 50 percent required today.

- Alternate method: Report a complete specialty measure set (not a small sample, which distinguishes this from the Measures Group method).

- All patients are included, not just Medicare Part B.

In short, although fewer measures are required, reporting requirements will be more challenging. With reporting becoming comprehensive, the idea of “incomplete” or “no response” is on its way out. In PQRS, it’s possible to report on 50 percent of eligible patients in a manner that performance doesn’t reflect reality. Many have figured out that it’s possible to artificially inflate performance by only reporting on patients where performance has been met. CMS has seen this, too, and is closing the loophole.

Like PQRS/VM, multiple options have been retained for data submission and reporting method. Those who wish to report as individuals can submit through a QCDR, Qualified Registry, their EHR, through claims or elect to have CMS calculate their scores through Administrative Claims. Those who elect Group Practice Reporting lose the option of claims, but gain the choice of the CMS Web Interface and the option of including the CAHPS for MIPS survey.

Resource Use

Those who have downloaded their Quality and Resource Use Reports (QRURs) know that their Value Modifier is derived from more than comparative measure performance. QRURs also include scores on cost and quality metrics based on CMS claims. This process continues under MIPS and is the foundation for the Resource Use category. At the core, the two “all beneficiary” per-capita cost metrics carry over:

- Per-Capita Costs for attributed patients, based on a two-step attribution methodology focused on which group is providing primary care services (similar to the existing process);

- Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary, to measure costs of care surrounding hospitalizations.

In addition to the broader categories, the Resource Use category will also examine specific sets of patients. For VM, Medicare looks at costs for patients who have been diagnosed with one or more of four conditions (Diabetes, Heart Failure, COPD and Coronary Artery Disease). Although the process is similar under MIPS, there is a ten-fold increase in what’s going under the microscope. Rather than four conditions, 41 episode-based measures have been proposed. Some focus on chronic conditions, while others look at procedures.

Many providers, particularly specialty physicians, have lamented that the four chronic conditions are inappropriate for calculating their performance—so this expanded set of measures is a clear response from CMS. Those who have downloaded and reviewed their supplemental QRURs (sQRURs) have a head start on what’s being tracked and how they compare.

Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA)

CPIA is the new kid on the block. This portion of the MIPS composite doesn’t originate in PQRS, VM or Meaningful Use. Its purpose is to create a framework for practices to improve and to earn credit for doing so. Scoring is based on point values assigned to “high,” “medium” and “low” approved activities, with “high” weighted activities earning the most points. Full credit may be achieved either by completing enough activities to earn at least 60 points or by participating in a Patient-Centered Medical Home or “comparable specialty practice.” MACRA specifies six categories of CPIAs:

- Expanded Practice Access

- Population Management

- Care Coordination

- Beneficiary Engagement

- Patients Safety and Practice Assessment

- Participation in an APM or Medical Home

In addition to these, three additional categories have been proposed:

- Achieving Health Equity

- Emergency Preparedness and Response

- Integrated Behavioral and Mental Health

Like the Quality component, CPIA may be reported as individuals or in groups, with the same options for each, but with one additional option: attestation, which may occur in conjunction with data submission, or not. Regardless of method, you are in charge of your CPIA score—whether earning zero, 60 or anything in between, your score is not compared to other practices.

Advancing Care Information (ACI)

The outgrowth of Meaningful Use, ACI is designed to ensure that Health Information Technology (HIT) is used “meaningfully” to exchange information. While it may sound just like Meaningful Use, the scoring has changed—to some extent, at least. The primary difference between ACI and Meaningful Use is what defines “meaningful.” MU defines it by process. Advancing Care Information rewards information exchange and patient engagement. As with CPIA, you are in control of your score. Unlike CPIA, you can earn 50 points (half of the total score) simply by reporting a numerator/denominator or yes/no for each performance standard.

What about the other half? In a departure from Meaningful Use, Advancing Care Information allows more flexibility for reporting. Instead of needing to meet thresholds in a pre-defined set of metrics, providers can succeed in ACI by selecting measures from one of three objectives:

- Patient Electronic Access

- Coordination of Care Through Patient Engagement

- Health Information Exchange

No longer are providers on the hook for reporting the same measures that are already required in other programs. The requirement of reporting eCQMs for MU in addition to (for many) the same measures for PQRS (but in another format) was redundant at best, and financially damaging at worse—plenty were penalized in PQRS who thought they’d fulfilled reporting requirements by submitting eCQMs for MU.

The Wild Cards

The methodology seems straightforward: each category is scored, each category is applied (in varying weight) to your composite score. That composite is compared to your peers, and payment adjustment is calculated accordingly.

You didn’t think you were going to get off that easy, did you?

Alternate Payment Model (APM) participation alters the playing field. Depending on whether the APM is considered an “Advanced APM” or a “MIPS APM,” the weights for some of these components may change, and in some cases, drop to zero (i.e. it will not be applied to your score). In some cases, groups can earn bonus points in certain categories. For example, an extra percentage point can be added to groups’ ACI scores if they report to a Clinical Data Registry (CDR).

So, now you can see why the MIPS Composite Performance Score is complicated—and why it pays to learn now how your score will be calculated. Six months may seem like a long time to sort this out, but 2017—the baseline year for 2019 performance adjustments—will be here sooner than you think. Time invested today in planning for MIPS will save big penalties in the future, and help your organization do an even better job of providing high quality care for the lowest cost.

Founded in 2002, ICLOPS has pioneered data registry solutions for improving patient health. Our industry experts provide comprehensive Solutions that help you both report and improve your performance. ICLOPS is a CMS Qualified Clinical Data Registry.

Contact ICLOPS for a Discovery Session.

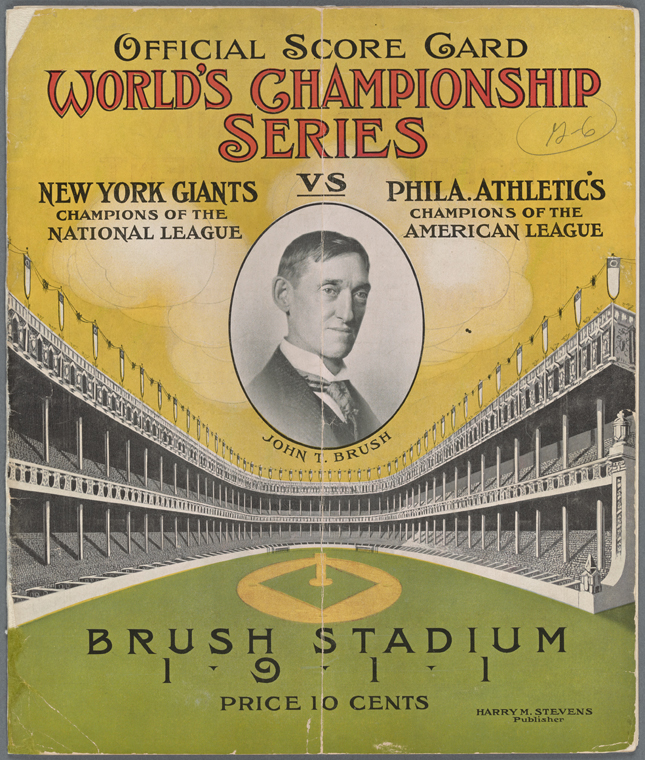

Image Credit: George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library. “Offical Score Card. World’s Championship Series. New York Giants vs Philadelphia Athletics” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1911.