Our articles on women’s health care issues have focused on areas that must change in order to provide better quality and outcomes, to lower costs, to advance treatment, and to treat women respectfully and equitably as patients and providers. We have demonstrated how women have been sidelined from getting the right health care because of two key systemic obstacles that must be addressed:

- Cultural bias that prevents accurate clinical assessment of symptoms and diagnosis, adoption or use of protocols relative to women’s biology, and effective health care therapies, and

- Inadequate basic science and clinical research that will illuminate sex-differentiated biology and effects of therapies.

In addressing women with autoimmune diseases, I expected to find the same story as in other clinical areas, just in greater magnitude. Instead, I found a different story. That story is about how women with autoimmune diseases are isolated not only by the often painful, debilitating and progressive symptoms of disease, but also by the need to navigate their care on their own.

The story also concerns another front where women with autoimmune diseases are literally fighting for their lives: access to the specialized health care that is essential to their complex, often rare disease, and lack of resources to pay for it. Our system of insurance-coverage-financed health care, especially as it moves to lower cost through Value-Based Health Care, must not only avoid further damaging access to the care these women need, but also proactively facilitate better coordination of services for this high-risk group.

Autoimmune diseases reveal how the financing of health care compounds the problems of sex-specific disease, on top of the issues presented in recent posts on other clinical areas. And, it reveals how essential it is to organize health care not just around traditional specialties, but also around the patient. We must ensure that our reimbursement methods and historical structures do not impede essential research that crosses all specialties; to do otherwise will restrict advancement of care for population groups that are inordinately affected.

Autoimmune Diseases Affect 8-16 Percent of Population—Almost 80 Percent are Women

Autoimmune diseases are a group of disparate diseases in which the body’s immune system has launched an attack on its healthy tissue. Genetics, environmental causes, injury or infection and exposure to toxins are all thought to play a role in triggering excessive immune system responses, but the causes specific to individual autoimmune diseases are, as yet, mostly unproven.

About 23.5 million Americans are counted among the 24 more common autoimmune diseases with an incidence of 1 or more per 10,000 people. However, the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association (AARDA)—the only organization tracking all such diseases—puts the estimates of people affected at 50 million when considering additional autoimmune diseases that are more rare and not well counted.

Women overwhelmingly account for most autoimmune disease cases and are 78 percent of the counted population volume. Sex hormones are linked with the incidence of autoimmune diseases among women. In rheumatoid arthritis and Hashimoto’s autoimmune thyroiditis, two diseases with the highest autoimmune-disease-specific incidence, women account for 75 percent and 95 percent of patients, respectively. Only one of the top 5 autoimmune diseases, Type 1 diabetes, has incidence that affects more men than women, who are still 45 percent of the population. The rarer diseases within the top 24 include systemic diseases such as scleroderma, SLE (lupus), and Sjögren’s syndrome; women account for between 88 and 97 percent of patients.

Lack of Aggregate Autoimmune Disease Classification Isolates Individual Conditions—and Their Women Patients

There are 80 to 100 diseases classified as autoimmune currently, and 40 additional are suspected as auto-immune. Yet just 24 diseases are counted among prevalent autoimmune diseases. The arbitrary cutoff for determining prevalence serves little helpful purpose to advocacy or medicine. The range of incidence in the list of 24 reflects vastly different volumes—a low incidence of 10 per 10,000 for the cardiovascular Kawasaki disease, to a high of 860 per 10,000 for rheumatoid arthritis. While this list may largely reflect more reliable data because volume gives rise to advocacy groups and tracking, it also obscures the effect of autoimmune diseases among patients, predominantly women.

Lack of a centralized locus of disease and symptom tracking, basic science and clinical research, and data sharing for autoimmune diseases stymies progress. It may also fragment the study of environmental and other underlying triggers as well as the immune system itself. Unlike cancers that fall within different body systems, autoimmune diseases are classified within specialties and remain invisibly tucked within the volume of other specialty conditions.

Disease classification also has implications for awareness among providers and patients, public health initiatives, and availability of research funding. Fragmented data cannot create the foundation needed for advocacy and political action, nor will it fuel protections for women under insurance coverage. Funding for cancer research and therapies, by contrast, is driven by a coordinated system of advocates and medicine and is fueled by public awareness. The numbers speak for themselves: $6.7 billion for cancer research, and $591 million for all autoimmune diseases annually.

Pain and Diverse Symptoms—Often Similar Across Different Diseases—Are Hallmarks of Autoimmune Diseases

Incidence of autoimmune disease is increasing dramatically, especially in endocrine, rheumatic and gastrointestinal disease. But regardless of body system, symptoms are frequently similar. Pain in joints and elsewhere is very common and can be severe, especially in diseases that affect women. Also typical are fatigue, weakness and/or paralysis, sensitivity to heat or cold, itching, and loss of functions such as mobility and swallowing.

Diversity of symptoms and lack of awareness by providers can lead to delayed diagnoses. That delay is likely to be complicated by well-documented underestimation of women in pain. On average, there is a three-year time frame between patients seeking diagnosis for symptoms and final diagnosis of an autoimmune disease, according to the AARDA.

In the case of autoimmune disease, chronic pain is distinguished from acute disease by its persistent and sometimes crippling intensity. Many providers resort to opioids in an attempt to help patients manage pain. In addition to addiction, opioids negatively impact long-term outcomes. A study of SLE about the impact of opioid use on outcomes in a population of patients, including 24 percent of subjects who were addicted to opioids, showed higher mortality and morbidity associated with opioid use. With women more likely to become addicted than men due to their higher incidence of chronic pain, there will be pressure to find other methods of managing these debilitating symptoms for women with autoimmune diseases.

Opioids can also suppress or stimulate the immune systems of autoimmune patients, depending on disease, drug and various characteristics of the immune system. Opioids can also cause inflammation and other effects on body systems. These findings raise serious questions for physicians regarding how to modulate immune system effects properly while addressing chronic pain, especially in light of insufficient instruments for better measuring pain and women’s higher susceptibility to addiction.

The American Chronic Pain Management Association provides information for consumers on diseases associated with chronic pain, plus a variety of tools for recognizing and reporting pain to providers. These useful tools could be helpful to patients and providers, especially if there were initiatives to help validate results and tie into resources for chronic pain management.

Navigating the Health Care System Challenges Women with Autoimmune Disease

The fact that there are relatively low numbers of individuals affected by these conditions yet significantly greater incidence among women makes it particularly difficult for women to find specialists for their condition. Let’s use the example of scleroderma, a systemic autoimmune disease that is relatively rare like most autoimmune diseases (affects 240 per million adults in the U.S. ), yet is one of the most prevalent autoimmune diseases.

Scleroderma can involve many body systems and therefore specialized medicine: in addition to finding a rheumatologist with (hopefully) specific expertise in scleroderma and access to clinical trials, a woman with scleroderma will probably seek a dermatologist and wound care, pulmonologist, cardiologist and nephrologist throughout the course of the disease. Even if she finds a team of specialists, however, not all those providers may have specific experience with scleroderma. In New York City, there are only two rheumatology groups recognized by the Scleroderma Foundation as treatment and research centers where specialists are familiar with all of the disease’s manifestations. One can only imagine how difficult it must be for an individual woman to navigate care in the typical system of non-coordinated care, particularly outside major population centers.

Then there’s the next hurdle, which may prove insurmountable: finding those physicians in a woman’s benefit network. Commercial networks have adopted tiered networks of providers based on costs or Accountable Care contracts, and specialized providers—especially in higher cost academic centers—are often excluded due to cost. Thus, in the New York City example, one or even both groups may be out of network, requiring the insured woman to pay a much greater proportion of the expense of getting appropriate care. That assumes the specialists will even see a patient covered by a plan with which they do not participate, since that exposes them to bad debt.

Women as a group are more likely to be underinsured or uninsured. If attempts to repeal some or all of the Affordable Care Act succeed, women diagnosed with autoimmune diseases as preexisting conditions will have no coverage. It is difficult to imagine how millions of women with autoimmune disease will get the treatment they need to function.

Beyond physicians, access to some services—often considered experimental—are not routinely covered by insurers. There may be “step therapy” requirements, whereby one type of treatment must fail before another can be authorized. This kind of requirement was just recently permitted for Medicare Advantage plans for their beneficiaries. Step therapy in cancer care means loss of valuable time, permitting tumor growth and potential death. Step therapy is the opposite of precision medicine, which designs care around individual needs in conjunction with the best and most recent research findings. For autoimmune disease, it can mean further progression of disease, onset of greater pain and debilitating illness, and huge impacts on productivity and quality of life.

Then There’s the High Cost of Drugs for Women with Systemic Autoimmune Diseases

Women with autoimmune diseases require not only specialized drugs for their illnesses but also must work through tolerance issues that most patients don’t need to fear. Because many drugs can have different effects on the immune system, afflicted women have to navigate options and use those determined to be most effective and with the least additional harm. That is a tall order.

Added to that is the rarity of autoimmune diseases and the agents available for treatment. Rare diseases involve rarer and highly expensive medicines, some of which are categorized in top tiers of drug formularies and require significant patient copays—or are not covered at all. This post by a woman recounting how to handle drug costs of scleroderma, as well as make other coverage choices, is a sobering first hand account of the financial issues that women with autoimmune diseases must manage .

While there are some drug assistance programs emerging, they are not enough to cover women across the country. The Autoimmune Advocacy Alliance (A3) provides advocacy to people with autoimmune diseases, including supporting public policy for prescription drug assistance. But this will continue to be an area of critical importance that must be addressed as part of health care reform.

Five Actions Providers Should Take to Help Women with Autoimmune Diseases

Health systems and ACOs must play an important role in improving outcomes for women with autoimmune diseases. While providers have focused their efforts on diseases with high mortality or mortality potential, our review of autoimmune disease reflects that women’s health concerns are often better measured by quality of life indicators, such as functionality and pain. Health care organizations cannot successfully conduct population health while excluding large groups of women, such as those with autoimmune disease.

Autoimmune diseases in the aggregate are enormously expensive, over twice the total annual cost of cancer, according to the AARDA. Total costs of care are estimated at about $100 billion annually, although many individual autoimmune disease organizations believe that is vastly understated. The cost of prescription drugs alone accounts for an estimated 20 percent of total annual specialty drug spending, and three of the top six drugs sold in 2015 were biological agents for autoimmune disease.

Health care economists often point to the fact that five percent of patients drive the majority of annual health care spending. But those patients are not at end-stage, research shows. These are patients suffering through a health crisis and recovering. Autoimmune diseases are often cyclical, with a long trajectory of flare-ups and quiescent periods. Women with autoimmune disease understand what they are up against.

An ACO or health system looking toward the future must address women with autoimmune diseases as a big priority, or costs as well as outcome will quickly be out of control.

Here are five steps to address the pressing needs of women with autoimmune diseases:

- Create a provider network that will serve patients with autoimmune diseases. Even with best design, however, some health systems and ACOs will lack adequate specialists to support coordinated care for all autoimmune diseases. They must be willing to create referral arrangements with other systems to provide this coverage.

- Establish or connect to programs to support prescription drug assistance. As drug costs continue to soar, health systems can use their connections to find financial assistance for patients needing expensive drugs, or participate in programs that offer such assistance.

- Create individual and family-centered coordination of care plans for patients with autoimmune disease, as part of population health. Patients should not have to navigate the system alone, but should understand who is available to help them make educated choices among specialty providers, help arrange their specialty panels after patients choose, if necessary, and ensure that women understand how they can communicate regularly with providers. Most important, their physicians should be educated in shared decision-making processes and have research data available to provide patients with reliable information on benefits and potential harms associated with each treatment.

- Emphasize data gathering and analytics to measure services to autoimmune patients, their outcomes and symptoms. Providers must play a role in capturing symptoms and functionality of their patients, to regularly monitor for outcomes improvement or decline. If the outcomes of autoimmune diseases, such as pain and functionality, are not routinely captured, the health system or ACO will not be capable of measuring the health of its services to patients. Also, academic centers with research capability should be capturing detailed electronic data on patient symptoms and reported outcomes, for potential research and analytics opportunities. Patient-reported outcomes, especially pain and functionality assessments, are critical to include in measurement of outcomes for auto-immune diseases.

- Help patients navigate financial coverage as well as care. While patient advocates may be limited to larger health systems and ACOs, all health care organizations can use care coordinators and other personnel to assist patients in the arduous tasks of ensuring the timely sequencing of a treatment plan.

Women with autoimmune diseases are an underserved population of patients and are challenging to help. But providers can take steps to recognize the legitimate needs of this important patient population and improve outcomes and cost performance during that process.

Founded as ICLOPS in 2002, Roji Health Intelligence guides health care systems, providers and patients on the path to better health through Solutions that help providers improve their value and succeed in Risk. Roji Health Intelligence is a CMS Qualified Clinical Data Registry.

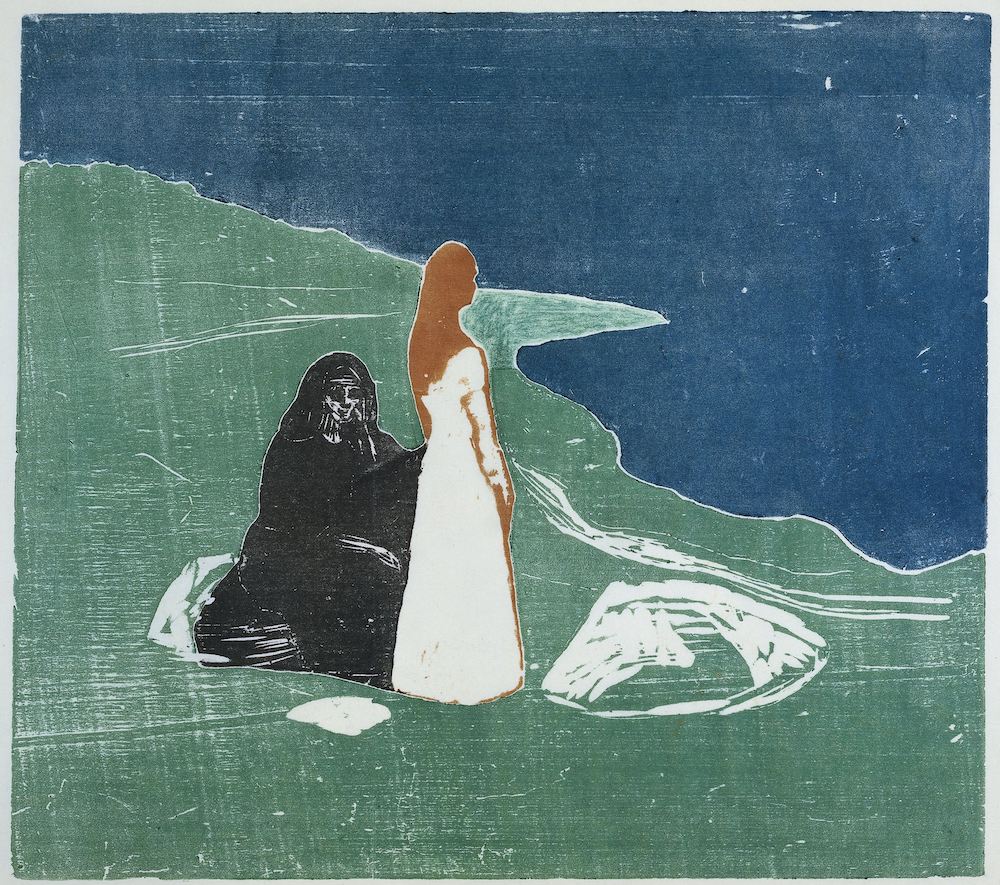

Image: Two Women on the Beach by Edvard Munch, 1898, color woodcut on paper, courtesy of the Rijksmuseum